A perpetual bond is a bond that has no maturity date – so the issuer of the bond pays coupons on the bond forever, but with no obligation to redeem the principal (ie amount borrowed).

What sort of magic is this?

A perpetual bond may sound like the ultimate ‘magic money tree’ - one that goes on bearing fruit forever. As is almost always the case, the truth is more complicated than that, but in this case, it’s no less intriguing.

In this blog I will introduce you to the perpetual bonds that I’ve owned my entire life. I consider whether buying perpetual bonds are a good investment and discuss whether modern governments should begin selling them in a similar spirit to the wartime bonds of old.

My perpetual bond

Fifty years ago, shortly after I was born, my father made an investment in perpetual government bonds in my name. These bonds sat in my father’s tin file until I came of age, at which point he handed them over to me. I promptly went out and bought a tin file of my own and the bonds remain stored there to this day.

The bonds in question are £4 worth of Premium Bonds; these are a form of perpetual bond because they have no expiration date. However, rather than paying out a regular coupon, the payout is the chance to win a large sum of money. The winning numbers are generated each month by ERNIE, the Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment. These numbers are authenticated and certified for randomness by GAD each month (so I’d need to declare a potential conflict of interest should I ever be asked to help out there).

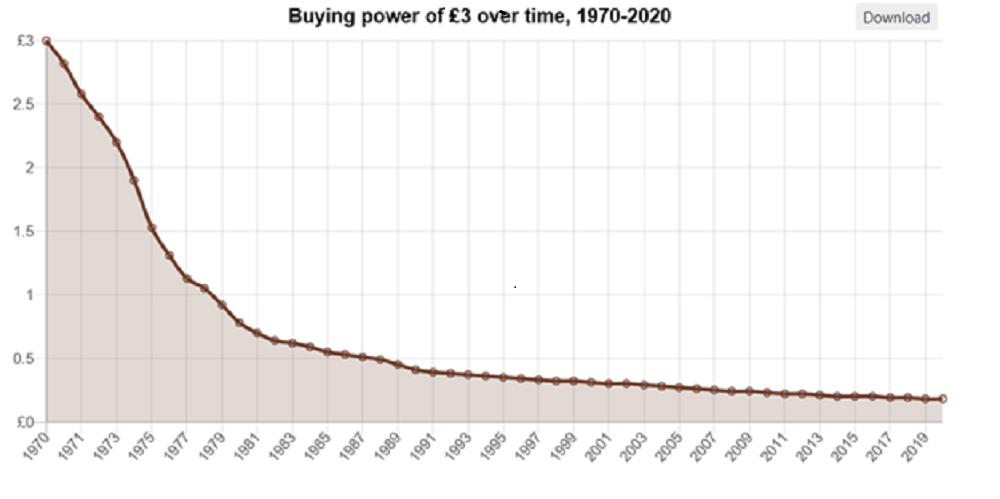

A few years ago, I read a newspaper article about there being millions of pounds worth of unclaimed prizes. I checked my bond holder’s number on the National Savings and Investment website, but there was no unclaimed prize waiting for me. The bonds are worth £4 today, just as they were the day my father purchased them nearly 50 years ago. However, £4 is not worth nearly as much today as it was back in 1970.

This shows us that the mortal enemy of perpetual bonds is inflation. That £4 my father put aside, if increased by inflation, should be worth about £60 today. Which doesn’t make it look like a very sensible allocation of funds. (However, if I was to win £1 million next month, one might think very differently. Interestingly, even though the value of the bond itself has not increased over time, the value of the prize pool has, and is currently being increased at a rate of 1.4% p.a.).

An alternative investment might have been for my father to have bought a fixed interest government bond back in 1970. Let’s say that such a bond paid 5% interest (as an example) and my father had bought this bond for me and made the coupons my pocket money. My allowance would have started at 20p, a sum that a young child in the 1970s would have been grateful to receive (roughly £3 in today’s money). But because there is no inflationary adjustment, the coupons would still be worth 20p today, enough to buy one lollipop at the corner shop.

If my father had invested the 5% coupons in an interest-bearing savings account that averaged 5% over the past 50 years, then the investment would be worth £46 today. A respectable sum, but it still hasn’t kept pace with inflation.

If my father had invested the £4 in equities, then we might expect to have made an average return of 6% to 8% a year over the past 50 years. This would have resulted in my fund being worth between £74 and £188 today. It could, of course, be worth nothing as investing in the stock exchange in 1970 wasn’t the simple matter of registering your details with a trading platform and buying a few units of an index tracking Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) that it is today. Back then, you needed to pick individual stocks and have a broker willing to make the trade on your behalf.

It’s possible that he could have picked a winner, such as Walmart, which went public in 1970. That £4 investment could have morphed into a fund worth close to £40k today. (Incidentally, you can always look online about the best stock pick from the year of your birth.) So, if a modern government was to decide to issue perpetual bonds to the public, the decision on whether or not to buy them will hinge largely on views of what inflation is likely to do over the long term and the possible alternative return on other investments.

How perpetual are Perpetual Bonds?

Governments have a long history of issuing bonds in times of crisis, such as the war bonds issued by the UK government between 1915 and 1917 paying out rates of interest from 3.5% to 5%. However, these bonds turned out not to be as perpetual as the name would suggest. In 2014 the UK government began to redeem old perpetual bonds, mostly dating back to World War I issues, but with some dating as far back as the Crimean and Napoleonic wars and even the South Sea Bubble crisis of 1720.

It should also be noted that at least some of these bond issues were not the resounding success that they were portrayed as in the press at the time. In particular, a recent Bank of England blog revealed that one particular World War I issue was undersubscribed, despite what was reported at the time, and that the Bank of England made up the shortfall.

However, there are some very good reasons why world governments may be tempted to use perpetual bonds as a tool in the current crisis. If a government is currently facing the costs and other challenges of rolling forward bond arrangements that it already has on the books, then it might consider taking advantage of interest rates being at historic lows and taking on arrangements that will never need to be rolled forward. There are, of course, perpetual corporate bonds, but that is a topic I will leave for a future blog!

1 comment

Comment by Paul posted on

Thank you Scott - an educational and entertaining item.