Firstly, let’s define what inflation is. For the purposes of this blog, I’ll give a broad definition for inflation as ‘the general increase in prices of goods and services.’

Therefore, negative inflation, commonly known as ‘deflation’, will refer to the general decrease in the price of goods and services – by which I mean things getting cheaper to buy over time.

Measuring it

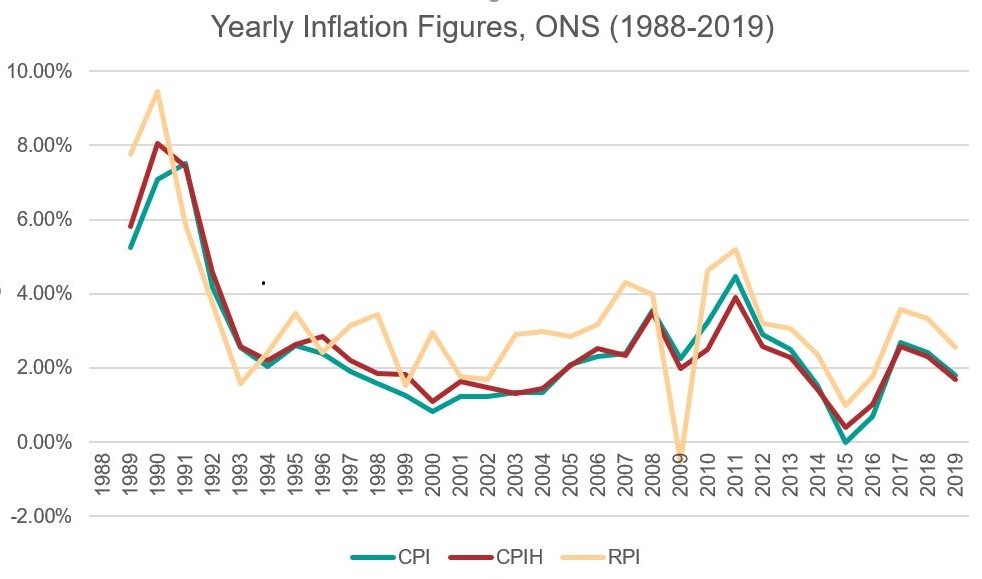

Because there are so many goods and services available in the economy, and different ways of calculating inflation, there is no single definitive measure. Instead, in the UK we have 3 main measures of inflation. These are the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) and Retail Prices Index (RPI).

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) calculates these indices by looking at something called a ‘weighted basket of goods and services’. The ONS picks around 700 goods and services and assigns them a weight.

This refers to how much they contribute to the basket – or in other words roughly how much the average household might spend on that good or service relative to everything else. The cost of this basket is then tracked to give a figure for inflation.

The differences between these indices are largely due to the differences in the goods and services selected and their weightings. For instance, CPIH includes goods and services associated with housing such as Council Tax, whereas CPI doesn’t. However, for RPI the calculation methodology is quite different (which is explained in more detail here.)

This has led to some noticeable differences between RPI and the other measures over the last 10 years or so, as demonstrated in the graph below.

The goods and services, including their weighting are reviewed periodically to reflect how we typically spend our money. For example, in 2019, the ONS added smart speakers and removed envelopes from their CPI calculations. Perhaps next year we might see hand-sanitiser or toilet paper being given a greater role!

We need to have a measure for inflation for 2 main reasons. Firstly, as an indicator for the general health of the economy, which helps consumers and businesses prepare for the future.

Secondly, some financial products, such as the state pension’s ‘triple lock’, may have costs and benefits which are directly tied to inflation figures.

Why does negative inflation occur?

Negative inflation can occur for many reasons, and in reality, it probably occurs from a combination of them. I’ll split them into 2 broad reasons: consumers demanding fewer goods and services which leads to lower prices, or producers offering goods and services at lower prices – for example because of efficiencies in their production process or trying to outdo competitors.

The factors that affect this supply and demand are far-reaching and intertwined, often including average earnings growth, interest rates, exchange rates and so on. You’d probably want an economist to untangle these.

Winners and losers

So, is negative inflation a good thing or not? From an initial glance, consumers are the winners here, as now their money can take them further than previously. I (among many others I’m sure) would be particularly happy if the weekly shop and monthly bills were a bit cheaper!

However, if negative inflation is persistent, the main loser will be the economy and ultimately individuals. Expectations of negative inflation may incentivise people to put off purchases now in the belief that they can get the items cheaper in the future.

Conversely, negative inflation caused by low levels of spending may be a symptom of a bigger economic problem, such as stagnating wages and unemployment.

Either way, this reduced spending from consumers leads to reduced profits for businesses who may ultimately reduce their staffing which would increase unemployment.

This can lead to further depression in consumer demand and so deflation can quickly become a vicious cycle that is hard for economies to get out of. For example, Japan’s battle with deflation and poor economic growth at the turn of the century lasted many years and is widely referred to as the “Lost Decade”.

COVID-19 and the outlook for the UK

The August 2020 figures give some concern for negative inflation as CPI was 0.2% which is well below the government target of 2.0%. This can be largely be attributed to falls in restaurant prices due to the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme and falling clothing and air travel prices, all of which are related to COVID-19.

COVID-19 has severely impacted the global economy and there is currently still a lot of uncertainty surrounding it and the future. Therefore, although the prospects of deflation seem higher than before the pandemic, it is still far too early and extremely difficult to predict how inflation might unfold in both the short-term and long-term.

Disclaimers

For further detail and expertise from GAD, see our Market data insights. The opinions in this blog post are not intended to provide specific advice. For our full disclaimer, please see the About this blog page.