The UK is already feeling the impacts of climate change with all 10 of the warmest years in the UK occurring since 2003. As the effects of climate change become more obvious, there is a growing urgency for public sector bodies to assess climate-related risks and understand how they might evolve in the future, so that they can manage these as effectively as possible. This is reflected in recent requirements for public sector bodies to produce climate-related financial disclosures in line with Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations.

At GAD we help public sector bodies assess their climate-related risks and create plans for how to mitigate them. As a department dedicated to actuarial work, GAD specialises in risk and uncertainty, so we are well placed to help with climate-related risk analysis.

Coming up, I look at the uncertainties associated with future climate change; from the emissions pathways we might take to how climate processes are modelled.

Later in this blog series we’ll consider the uncertainty in quantifying the financial impact of climate change. Recognising and clearly articulating uncertainties in our analysis is crucial to inform good decision making, avoid unsuitable adaptation action and increase our resilience to climate change over the coming decades.

What we mean by uncertainty

We don't know exactly how the climate will change in the future. Several factors can influence the climate, and we don't have perfect knowledge about how they interact or how they will change. Although, scientists can make predictions about future climate conditions using climate models, there will always be some unknowns.

Uncertainty related to future climate change can be broadly categorised into 3 areas, and I'll discuss each area in more detail below.

Scenario uncertainty

Scenario uncertainty refers to the unpredictability of future human activities and their impact on the climate. Factors could include:

- changes in technology

- policy decisions

- societal behaviour

All these could influence the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere over time.

Multiple possible futures

Scenario uncertainty is often explored by considering multiple possible futures. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is the UN body responsible for assessing science related to climate change. The IPCC uses different socioeconomic and emissions pathways to examine how the climate might change.

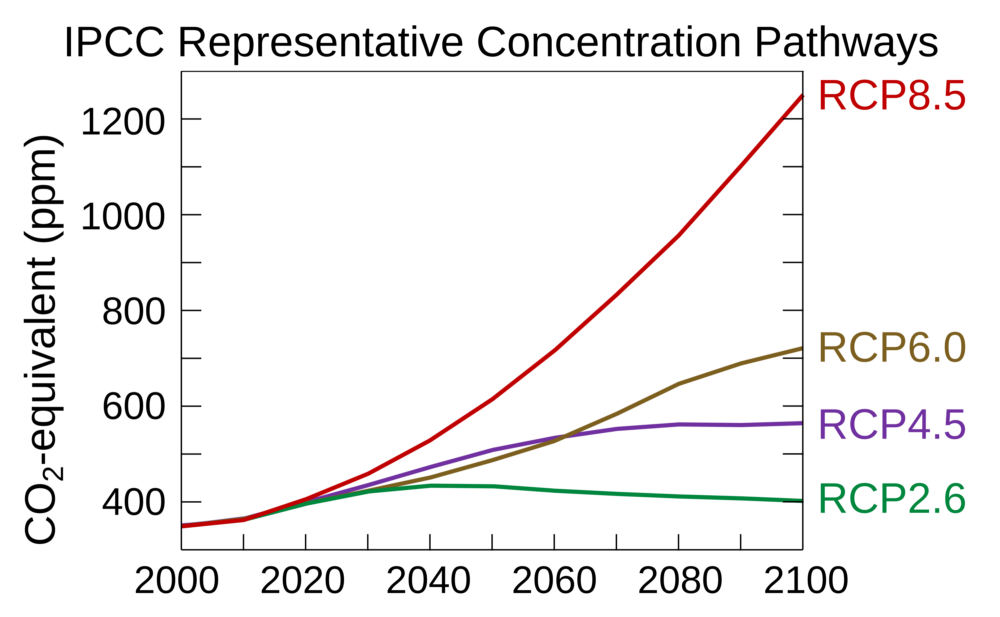

The IPCC bases its scenarios on different assumptions about future human activity and the impact these could have on greenhouse gas concentrations over time (Figure 1 below). It is important to look over a wide range of scenarios to get a more comprehensive understanding of the future changes we may face.

Figure 1: Different Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) are associated with different trajectories of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere and have been used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change to explore how the climate may change under different scenarios. Source: Wikipedia.

Model uncertainty

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” George Box, British statistician.

Climate models are complex computer simulations of factors that can affect the Earth’s climate including the atmosphere, oceans, ice and land. These factors include greenhouse gas emissions, solar radiation, ocean currents and cloud cover. The models can be used to recreate past climate or predict how the climate might change in future.

There is uncertainty associated with the outputs from climate models due to limitations in our understanding of the Earth’s systems and how they respond to greenhouse gas emissions, how models are designed, and the data inputs into the models. This type of uncertainty is often referred to as ‘model uncertainty’.

As an example, different climate models use different approaches and assumptions to represent the Earth’s physical, chemical and biological processes. These differences can lead to variations in the outputs generated from different climate models.

Model uncertainty is often examined by looking at a multi-model ensemble. This involves aggregating data from many different climate models to better understand the range of possible climate outcomes. This approach can better identify robust trends that are consistent across different models and provide a more reliable understanding of future climate change. Such methods are used in climate detection, attribution and impact studies that feed into the IPCC’s assessment of climate change.

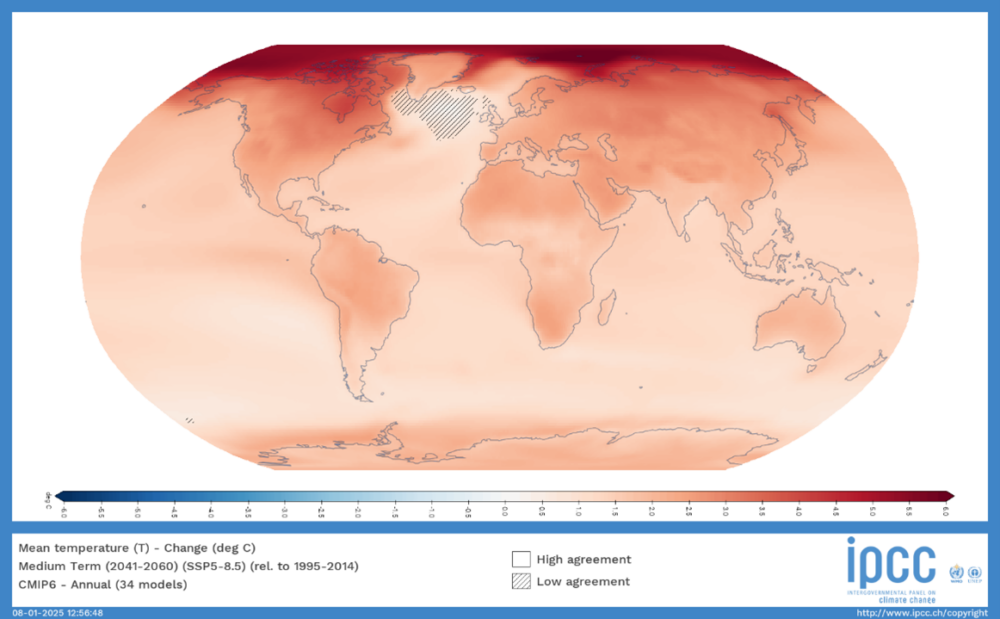

Average temperature projections from different climate models are often in good agreement (illustrated in Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: projected mean temperature change from baseline period (1995 - 2014) to the medium term (2041 -2060) under a high emissions scenario (SSP5 -8.5). Hashed area represents where there is low agreement between different global climate models, meaning that fewer than 80% of models agree on sign of change (temperature changes are calculated from 34 models). Source: IPCC.

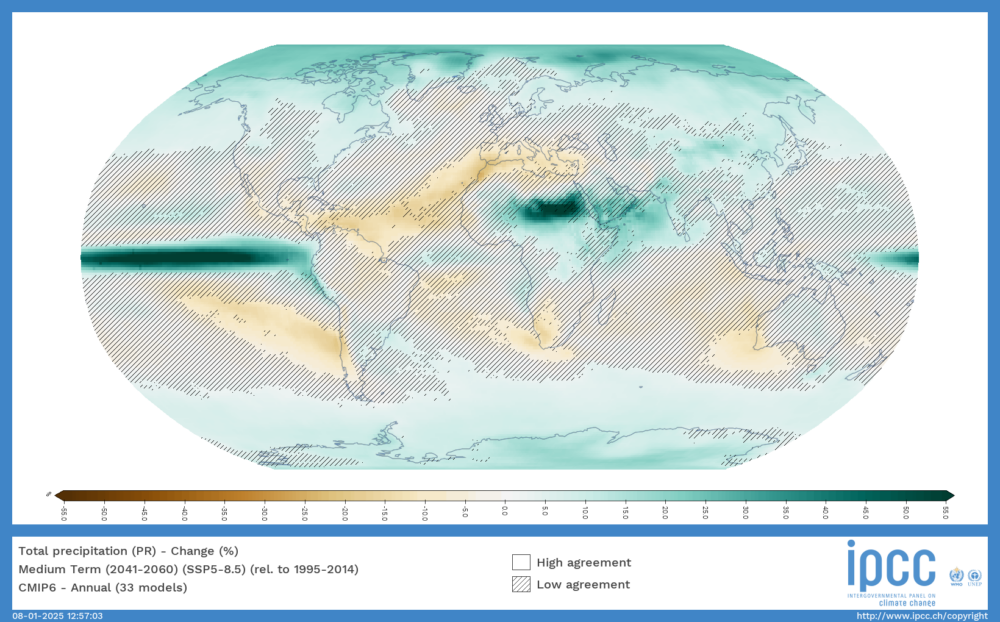

However, projections of other variables, including those related to rainfall, can sometimes differ significantly in some locations, meaning there is more uncertainty associated with how these climate properties may change at those locations (illustrated in Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: projected percentage change in total precipitation from baseline period (1995 - 2014) to the medium term (2041 -2060) under a high emissions scenario (SSP5 -8.5). Hashed area represents where there is low agreement between different global climate models, meaning that fewer than 80% of models agree on sign of change (precipitation changes are calculated from 33 models). Source: IPCC.

Model uncertainty can be reduced by increasing our scientific knowledge of how the Earth’s processes work and improving our models. However, it can never be eliminated since it’s impossible to build a model that fully reflects the complexity and intricacy of our reality.

Natural variability

Natural variability refers to uncertainty in the climate system due to natural processes such as:

- volcanic eruptions

- solar radiation fluctuations

- ocean-atmosphere interactions (such as El Niño and La Niña events) …

… rather than human influence.

These natural variations can cause short-term and often unpredictable fluctuations in climate patterns. They are a major cause of year-to-year changes in climate, even influencing trends over multiple years. This type of uncertainty can make it challenging to predict longer-term trends accurately.

The influence of natural variability is however typically small over periods of multiple decades. Climate model outputs are often averaged over multiple decades (as in figures 2 and 3) to help smooth out some of these shorter-term variations and more readily detect underlying longer-term trends.

It is difficult to reduce the inherent uncertainty associated with natural variability and therefore, it must be acknowledged in analysis and decision making.

How we can communicate uncertainty

Now we know about the uncertainty associated with climate model data and understand that it cannot ever be completely removed, we need to get comfortable living with it and ensuring it is communicated effectively.

There is no one correct way of communicating the uncertainty associated with a climate analysis, but as David Spiegelhalter highlights in his recent book, “The Art of Uncertainty, How to Navigate Change, Ignorance, Risk and Luck”, it is critical to do so to foster trust in our findings and improve decision making.

Here are some useful principals for communicating the uncertainty associated with climate analysis:

- recognise that uncertainty is unavoidable whenever analysing what might happen in the future

- identify sources of uncertainty within your analysis including related to the climate data you use

- explain clearly what these uncertainties are and if and how they have been mitigated

- clearly show where assumptions have been made and the impact of those assumptions on your results and conclusions

- indicate what supports your assumptions (body of literature, expert judgment etc.) and, if possible, assess any uncertainty associated with them

- finally, openly state the limitations of your analysis given the uncertainties you have identified

Further insights on how to present and communicate uncertainty in all kinds of analysis can be found in the Uncertainty Toolkit for Analysts in Government.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are the author’s own and the opinions in this blog post are not intended to provide specific advice. For our full disclaimer, please see the About this blog page.

Recent Comments