‘Net zero’ has become a buzz-phrase for climate-conscious companies over the past few years and has also infiltrated the world of investing. However, when it comes to investing, net zero targets are perhaps not the saviour that they seem to be in the corporate world.

In this blog I’ll look at what emissions investors are responsible for, whether investors can really make their portfolio net zero, and what the consequences could be.

The number of companies making net zero targets in line with the Science Based Targets Initiative is growing significantly every year:

First, let’s get on the same page about what net zero means. It is achieved by reducing the amount of carbon that is emitted into our atmosphere, and also extracting emissions from the atmosphere (hence the ‘net’).

Since the Paris Agreement in 2015 and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius in 2017, the term net zero has become ubiquitous in climate discussions.

It is generally well accepted that in order to keep global warming to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (as set out in the Paris Agreement), we must reach global net zero emissions by 2050, and ideally earlier.

An investor’s main source of emissions is from the companies in their investment portfolio that they either own (as in equity) or lend to (for debt and fixed income investments). Or it could be from the 'real’, or physical assets that they own in full or in part (such as for example, real estate or infrastructure.)

These are known as an investor’s financed emissions.

Knowing your emissions – scopes 1, 2 and 3

To understand becoming net zero, we first have to understand a little about what emissions are, and where they come from.

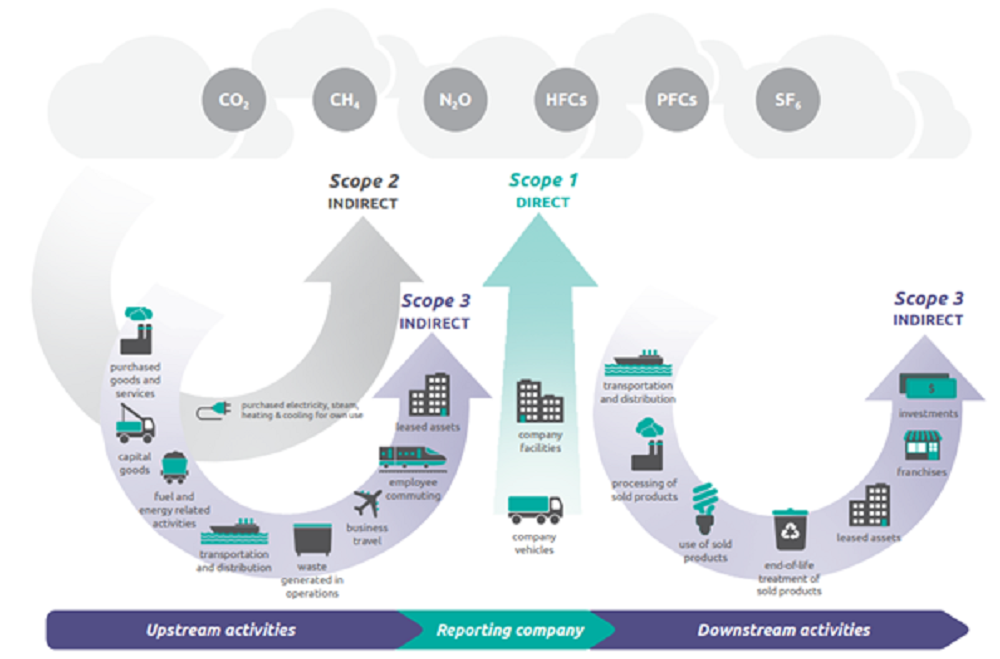

The term ‘carbon emissions’ is sometimes used to incorporate other greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane, nitrous oxide and chloroflourocarbons, among others.

Essentially, greenhouse gasses are those that contribute to the greenhouse effect of the planet by absorbing infrared radiation. All of these gasses are commonly combined into a single measure called carbon dioxide equivalent, also known as CO2e or carbon emissions. CO2e accounts for the fact that some gasses trap more heat than carbon dioxide but don’t stay in the atmosphere for as long.

When we assess the carbon emissions of a company, we split them into 3 'scopes', as shown below.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions sources

Scope 1 and 2 emissions (from company facilities and vehicles and from purchase energy) are relatively easy for companies to calculate. These emissions are generally within a company’s control and oversight.

Scope 3 emissions on the other hand are those that are generated:

- upstream (by employees commuting, business travel, the emissions embedded in purchased goods and services)

- downstream (transporting and distributing products, investments, use of sold products)

These emissions are more difficult to calculate because companies have less oversight of them. They tend to be the scope 1 and 2 emissions of their vendors or distributors.

They may also depend on factors outside of a company’s control. Take for example a car manufacturer; their scope 3 emissions will depend on how many miles are driven each year in the cars that they sell.

This means that to estimate their scope 3 emissions companies need to make an assumption about how their product will be used. Therefore, scope 3 emissions are often based on estimates and assumptions.

What are investors’ emissions?

Investors, such as pension schemes, endowments, charities, family offices and individuals, have emissions attributed to them like everyone else.

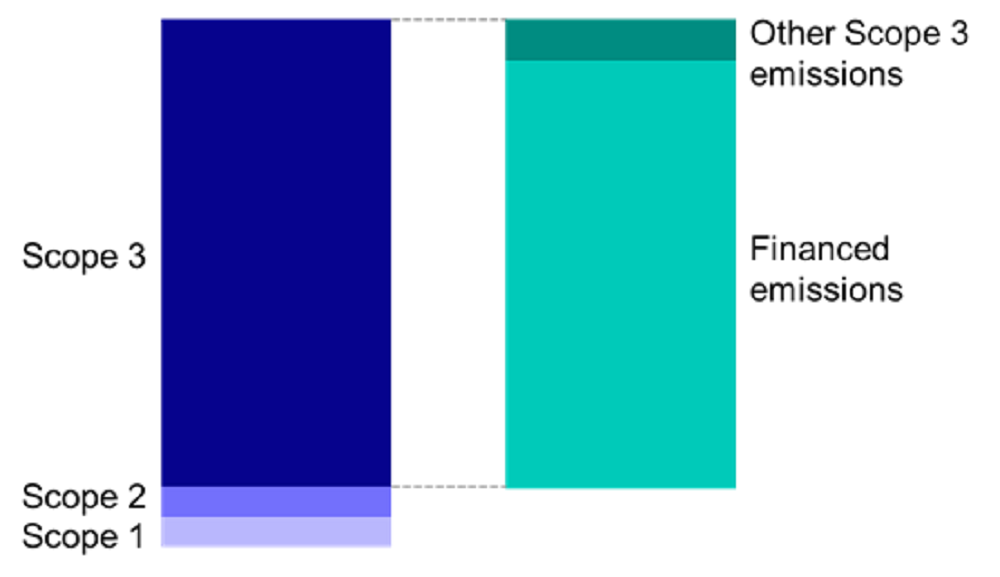

Institutional investors’ emissions tend to sit mainly within their scope 3 'investments’ category due to their financed emissions.

However, they also generate emissions in the same way that other businesses do in relation to business travel, company facilities or energy use. An illustration of a pension scheme’s emissions is set out below.

Illustration of pension scheme’s emissions

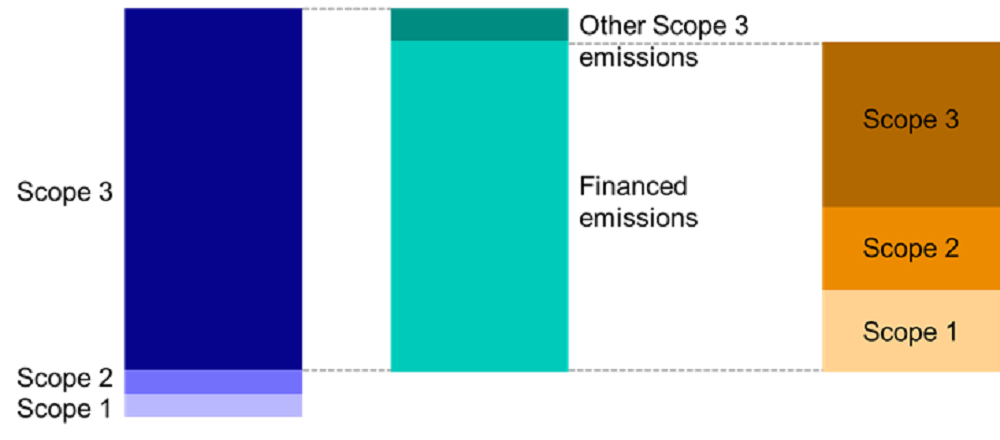

It gets more complicated when you look at the scopes of emissions within the financed emissions. These will include the scopes 1 to 3 emissions from their investee companies. For example, if a pension scheme holds equity in a particular company, it will be exposed to that company’s scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

Illustration of breakdown of pension scheme’s financed emissions

For simplicity in the rest of this blog, I’m going to concentrate on financed emissions; the emissions of the investment portfolio, only. Therefore, when I talk about an investor’s scope 3 emissions, I mean the scope 3 emissions of all of the companies they invest in.

Can investors control their financed emissions?

Investors, particularly institutional investors like pension scheme trustees and endowment investment committees, generally have a fiduciary responsibility to invest money in the best interests of the beneficiaries (such as pension scheme members).

They are obliged within this fiduciary duty to take into account financial factors which are relevant to balancing risks and returns, of which climate change is one.

To translate this: climate change poses a risk to the return that could be generated by investments. Therefore investors must take this risk into account in deciding how to invest.

It follows that investors may want to reduce their investments’ exposure to climate risk. One way of doing this may involve reducing the investments’ emissions, as a proxy for climate risk.

A key issue for investors to contend with is how they balance the exposure to climate risk with their other investment objectives, like generating an appropriate return for an acceptable level of risk. Cash under the mattress will give a low emissions portfolio, but won’t generate a return.

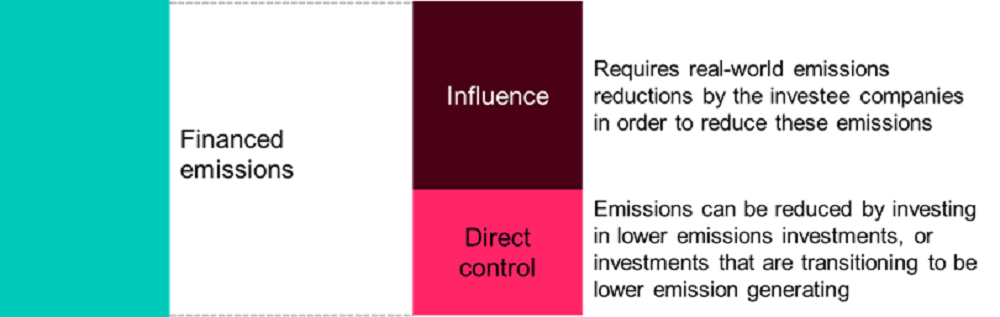

So, let’s assume that investors invest in assets such as equities and bonds. Doing so gives an investor some influence over the company that they invest in. For example, owning shares in a company gives you the right to vote at the company’s annual general meeting.

However, you are not making the day-to-day management decisions of that company, such as if or how the company decides to reduce its emissions. Therefore, the ability of an investor to control their investee companies’ emissions becomes somewhat limited, as illustrated below.

Illustration of investors control over financed emissions

When an investor sets a net zero target, they must understand that in order to meet that target, they have to place a reliance on the overall economy (particularly the universe of investible companies) decarbonising.

Otherwise, they won’t have any companies to invest in and maintain their net zero target.

It is for this reason (setting a target that you don’t have full control over) that there are some unintended consequences to net zero commitments that investors should understand before committing.

The unintended consequences of a net zero target for investors

I think the intentions behind investors setting net zero targets are admirable; sending a signal – to companies, to investment managers, to governments – that you won’t continue to invest in high emitting companies or investments.

An article in a recent edition of Professional Pensions read: “the question is whether a scheme views net zero as a carbon accounting exercise or a driver for real world change” (Jordan Griffiths, Barnett Waddingham).

Managing a net zero commitment should be balanced with the potential unintended consequences of setting such a target.

1 An aggressive net zero target can shrink your investible universe.

While setting a 2050 net zero target today may not have a huge impact on the number of companies you can invest in, as shown in the illustration above, investors are somewhat at the mercy of real-world decarbonisation to drive down their portfolio emissions. If that doesn’t happen, you could be left with a limited pool of companies to invest in in 10 to 20 years’ time.

That could mean giving up what is widely regarded as the only free lunch in investing – diversification. This is an essential tool for investors in controlling their investment risk.

If investors wanted to be net zero by 2025, say, they would end up with an extremely concentrated portfolio. That would increase their investment risk and could potentially compromise their fiduciary responsibility to their members.

2. A net zero target could stop you investing in real world emissions reduction.

I will illustrate this by an example. Renewable energy infrastructure provides a low emissions energy source. However, carbon is emitted throughout the renewable energy lifecycle, particularly at the beginning due to manufacture and construction. Then later through the maintenance and decommissioning processes.

Therefore, an investment strategy targeting net zero emissions in the short term, may find it difficult to make an investment in a new renewable energy infrastructure. This is even though this type of asset is designed to mitigate climate risk by reducing emissions overall.

Another example is the seemingly age-old ‘engage’ versus ‘divest’ debate. I think there are good arguments on either side of this and the decisions are nuanced.

The ‘engage’ argument says that by owning a high-emitting company and engaging with them actively to help them reduce their emissions, investors may have a greater real-world emissions impact than simply by divesting from that company and handing the ownership to another investor (who may not be as engaged in trying to reduce the company’s emissions.)

3. Lack of good scope 3 data may lead to moving investments from companies with high scope 1 and 2 to those with high scope 3 emissions.

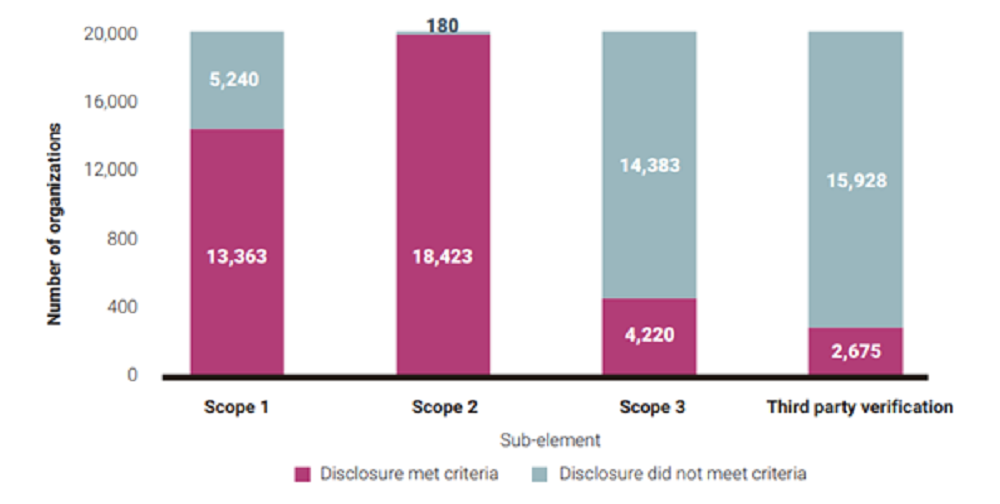

Scope 3 emissions data from companies is still lacking (see chart below). This may lead investors to set a net zero target based on scopes 1 and 2 emissions alone. This could lead to investing more in companies with low scopes 1 and 2 emissions, but high scope 3 emissions, and investing less in companies with high scopes 1 and 2 emissions, but low scope 3 emissions.

Scope 3 emissions are by far the least disclosed scope of emissions

Oil and gas companies for example, have relatively low scope 1 and 2 emissions in their production phase compared to their scope 3 product emissions.

Therefore, as a paper by the asset manager Storebrand explains, when investors are aiming to reduce real-world carbon emissions, “it is important that companies assess and incorporate their full value chain, including scope 3, into their targets”. I would argue the same is true of investors.

Summary: How investors can avoid the pitfalls of net zero investing

I hope this blog has shown that, unfortunately, there is no easy answer when it comes to net zero and climate-conscious investing.

I also hope that if you’re an investor struggling with questions around what the best sustainable investing approach to take is, you feel less alone in that struggle.

Investment decisions around climate change risk are nuanced and will only be vindicated with hindsight and the right time horizon.

I wanted to end with a few actions that investors can take now to help get a handle on their climate exposure, and what to do about it:

- Be clear about what you’re trying to do – Be aware that reducing your investment portfolio’s exposure to climate risk may mean a very different approach to using your investments to help fund a reduction in real-world climate risk. Make sure that whatever approach you take, it matches your ambition.

- Think about whether you really need to set a net zero target – Is a net zero target necessary or beneficial, or is there another target that might be more appropriate and that you can have more control over? This could be for example a target around the amount of type of engagement with investee companies that you can push your investment manager towards.

- Climate risk encompasses more than emissions alone – There are some cases where greater emissions now may lead to a significant reduction in emissions in future. So, investing in new renewable energy infrastructure could be emissions intensive in the short-term, build phase, but will help mitigate climate risk in the long term.

- Track your emissions over time as required by recommendations from the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures - TCFD. Also concentrate on the attribution of change in emissions – Understand the reasons for any changes to your financed emissions. Have they gone down because the companies you invest in have become more sustainable (which would be positive)? Or is it because your asset allocation has changed to favour more low emitting asset classes/sectors/companies and was this an active decision?

- Understand your investment managers’ strategies when it comes to reducing emissions – Are they planning to only invest in low emitters, or will they invest in high emitters now and engage with them to help them to reduce their emissions?

- Document your decisions and your reasoning – The world of climate investing changes quickly, and the membership of investment committees and trustee boards change over time. Documenting not only your decisions around sustainability but the reasoning behind them helps to know when the decision remains valid or when the surrounding situation has changed such that the decision should be revisited.

Disclaimer

The opinions in this blog post are not intended to provide specific advice. For our full disclaimer, please see the About this blog page.

Recent Comments